Peace Practice Series

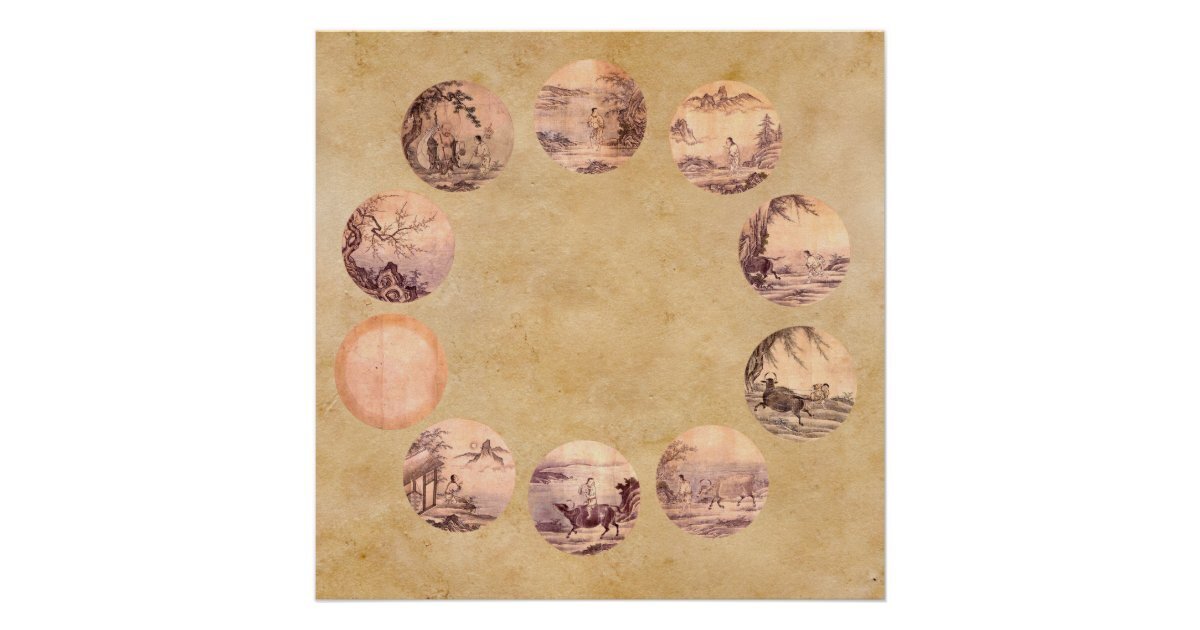

Zen Practice Series

1. Searching for the Ox

In the pasture of the world,

I endlessly push aside the tall

grasses in search of the Ox.

Following unnamed rivers,

lost upon the interpenetrating

paths of distant mountains,

My strength failing and my vitality

exhausted, I cannot find the Ox.

Zen Ox herding pictures - a template of process

In the following comments, while we speak of ‘phases’, they shouldn’t be thought of as a check list of levels that we complete and move on to the next one. All the ‘phases’ are present from the beginning.

Ox herding 1,2,3 - The Path of practice/effort, with a goal.

In our initial phase of practice, we seek the signs of the Ox … the fleeting traces of our inherent awakened ‘original mind’ or ‘Buddha nature’ or ‘Unborn’ essential Self.

We engage in the study of texts, scriptures and readings supportive and descriptive of how to discover and engage in this path of inner awakening and apply great effort in our meditation discipline.

This study/practice phase inspires and motivates us providing us fuel to go forward on our discovery on the path of awakening.

Central to keep in View: the ego naturally exhausts its quest to discover an external objective in ‘finding the Ox’. (In formal Zen through experiencing ‘great doubt’ in koan life/practice) Ultimately, ‘Nowhere to go, nothing to find’, yet the ‘nowhere’ and ‘nothing’ are unfathomable and ungraspable by the limited objectified self or ego. The ‘unfathomable’ is still seen as external in this phase… something the ‘I’ thinks it can discover and ‘achieve’. This planar two-dimensional phase of practice, organically grows more fully embodied to where it can go no further. The ego is fully exposed and releases its internal need for control of outcomes in relationship to Awakening. This integration is through our ‘unknowing’ zazen process and opens the next phase. (4,5,6)

2. Discovery of the Footprints / Seeing the Traces

Along the riverbank under the trees,

I discover footprints.

Even under the fragrant grass,

I see his prints.

Deep in remote mountains

they are found.

These traces can no more be hidden

than one’s nose, looking heavenward.

Oxherding 4,5,6

Here, we face the dilemma that our book and intellectual study no longer are sufficient to guide us. The pinpricks of satori become part of the tapestry of our daily experience. Meditation ‘practice’ is experienced more embodied and present. Breath, body, awareness are more unified, seamless and fluid. We move beyond the fear of ‘loss of self’.

While this study mode remains, a kind of reversal takes place where more and more our direct experience is in the forefront and our study has more the effect to verify rather than guide us. We begin to experience when the ‘unfathomable’ spontaneously embraces us. ‘Loss of self’ is welcome.

Our central motivation gradually shifts on a deeper level: our experience of ‘self’ moves beyond our mere self-identification or self-objectification, spontaneously arising with compassion for others.

Oxherding 7,8,9

Self and other become an experiential unified whole and ‘self’ effortlessly converges with the ‘unfathomable’. Here, the ‘ego’ is no longer driving or seeking. There is the Absolute presence of suchness (tathatha). Contemplation and compassion are integral.

Oxherding 10

Self / other (‘unfathomable’) is completely non dual. The relative ‘self’ and absolute ‘selfless self’ is experienced and viewed as having ‘never been separate’ -- ‘not one / not two’.

The Unborn:

never born, never dies.

3. Seeing the Ox

I hear the song of the nightingale.

The sun is warm, the wind is mild,

willows are green along the shore –

Here no Ox can hide!

What artist can draw that massive head,

those majestic horns?

In a completely organic way, the next phase begins to dawn more clearly. The inter relationship between ‘self’ and the objects of our experience gradually becomes more seamless interspersed with pinprick moments of suchness / satori.

4. Catching the Ox

I seize him with a terrific struggle.

His great will and power

are inexhaustible.

He charges to the high plateau

far above the cloud-mists,

Or in an impenetrable ravine he stands.

5.Taming the Bull / Herding the Ox

The whip and rope are necessary,

Else he might stray off down

some dusty road.

Being well-trained, he becomes

naturally gentle.

Then, unfettered, he obeys his master.

6. Riding the Ox Back Home

Mounting the Ox, slowly

I return homeward.

The voice of my flute intones

through the evening.

Measuring with hand-beats

the pulsating harmony,

I direct the endless rhythm.

Whoever hears this melody

will join me.

7. The Bull Transcended / The Ox Forgotten

Astride the Ox, I reach home.

I am serene. The Ox too can rest.

The dawn has come. In blissful repose,

Within my thatched dwelling

I have abandoned the whip and ropes.

8. Both Ox and Self Transcended

Whip, rope, person, and Ox –

all merge in No Thing.

This heaven is so vast,

no message can stain it.

How may a snowflake exist

in a raging fire.

Here are the footprints of

the Ancestors.

9. Returning to the Origin, Back to the Source

Too many steps have been taken

returning to the root and the source.

Better to have been blind and deaf

from the beginning!

Dwelling in one’s true abode,

unconcerned with and without –

The river flows tranquilly on

and the flowers are red.

10. Entering the Market Place with Compassionate Hands

Barefooted and naked of breast,

I mingle with the people of the world.

My clothes are ragged and dust-laden,

and I am ever blissful.

I use no magic to extend my life;

Now, before me, the dead trees

become alive.

The Zen Koan by Thomas Merton

(in process of adding the page scans 11/24 Ed.)

Introductory Note

This typescript copy of The Zen Koan (1) by Thomas Merton was mailed in 1965 to W. Y. Evans-Wentz (1878-1965). During his final years, Evans-Wentz was living at the Self Realization Fellowship in Encinitas and this copy was among his papers. There is an historical reference where the poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti writes to Merton seeking the address of ‘that Evans-Wentz man’. Merton had copies with marginalia notes of Evans-Wentz books, Tibetan Yoga and Secret Doctrines and Tibet’s Great Yogī Milarepa. These indirect links may explain how Evans-Wentz came to receive a copy of Thomas Merton’s ‘The Zen Koan’.

Thomas Merton with D.T. Suzuki New York 1964

1 - Lomaland Theosophy Archive document

Dana Paramita - Gateway to Inner Peace

and Outer Harmony

“I wish to become like a tree

shading all beings.”

- Yamada Koun Roshi

“In giving [dana], mind transforms the gift and the gift transforms mind.” – Zen Master Dogen

Introduction

Dana / Generosity is the foundation and seed of spiritual development. When practiced in its authentic depth, our self-centered bias, prejudice and judgmental obscurations are cut through. Zen Master Dogen[i] shares that “in giving [dana], mind transforms the gift and the gift transforms mind.” The dana paramita giving practice, subdues and cuts through our clinging and self-grasping opening more clarity of mind and compassionate activity.

In the process of being born and dying there is intrinsically the expression of the dana paramita. As Dogen, the founder of Soto Zen, writes regarding giving and the way of the Bodhisattva:

“When one learns well, being born and dying are both giving (dana)”

The dana paramita is a key to opening the essential heart essence of our Buddha nature. Dana practice is one of utter simplicity and directness and can be engaged in at any moment of the day where all expressions of speech and sharing are opportunities for dana practice. The most mundane aspects of our daily life provide endless opportunities for dana practice, whether sweeping the walkway, watering our garden or cleaning the kitchen. A pitfall can sometimes be a fabricated kind of scrupulous constriction or overly zealous kind of application. A deeper view of dana cuts through this kind of ego attached ‘giving’. Engaging in generosity without expectation of reward, we give without attaching to either the gift, the act of giving or who the receiver is. Our practice of generosity freely and spontaneously releases our self-binding and self-clinging obscurations on the way to awakening.

A story from early Chinese Ch’an Buddhist tradition expresses the view of dana as a direct gateway that cuts beyond our dualistic bias and self-delusion.

“A monk asked Hui-hai[ii] - ‘By what means can the gateway of our school be entered?

Hui-hai said, ‘By means of the Dana paramita.’

The monk said - ‘… why have you mentioned only the one? Please explain why only this one provides a sufficient means for us to enter?’

Hui-hai said, ‘Deluded people fail to understand that the other five [7 or ten] proceed from the Dana Paramita and that by its practice the others are fulfilled.’

Monk – ‘Why is it called Dana Paramita?’

Hui-hai – ‘Dana means relinquishment.’

Monk – ‘Relinquishment of what?’

Hui-hai – ‘Relinquishment of the dualism of opposites…

A: It means total relinquishment of ideas as to the dual nature of good and bad, being and nonbeing, love and aversion, void and non-void, concentration and distraction, pure and impure. By giving all of them up, we attain to a state in which all opposites are seen as void. The real practice of the Dana paramita entails achieving this state without any thought of 'now I see that opposites are void', or 'now I have relinquished all of them'. We may also call it 'the simultaneous cutting off of the myriad types of concurrent causes'; for it is when these are cut off that the whole Dharma-nature becomes void; and this voidness of the Dharma-nature means the non-dwelling of the mind upon anything whatsoever. Once that state is achieved, not a single form can be discerned. Why? Because our self-nature is immaterial and does not contain a single thing (foreign to itself). That which contains no single thing is true reality, the marvelous form of the Tathágata—it is said in the Diamond Sutra: 'Those who relinquish all forms are called "Buddhas" (enlightened ones).'

Q: However, the Buddha did speak of six paramitas, so why do you now say they can all be fulfilled in that one? Please give your reason for this.

A: The Sutra of the Questions of Brahma says: 'Jala-vidya, the elder, spoke unto Brahma and said, Bodhisattvas by relinquishing all defilement's (klesha) may be said to have fulfilled the Dana paramita, also known as 'total relinquishment'; being beguiled by nothing, they may be said to have fulfilled the síla paramita, also known as 'observing the precepts'; being hurt by nothing, they may be said to have fulfilled the kshanti paramita, also known as 'exercising forbearance'; clinging to nothing, they may be said to have fulfilled the virya paramita, also known as 'exercising zeal'; dwelling on nothing, they may be said to have fulfilled the Dhyana paramita, also known as 'practicing Dhyana and samádhi'; speaking lightly of nothing, they may be said to have fulfilled the prajña paramita, also known as 'exercising wisdom'. Together, they are named 'the six methods'. Now I am going to speak about those six methods in a way which means precisely the same—the first entails relinquishment; the second, no arising (of perception, sensation, etc); the third, no thinking; the fourth, remaining apart from forms; the fifth, non-abiding (of the mind); and the sixth, no indulgence in light speech. We give different names to these six methods only for convenience in dealing with passing needs; for, when we come to the marvelous principle involved in them all, we find no differences at all. So, you have only to understand that, by a single act of relinquishment, everything is relinquished; and that no arising means no arising of anything whatsoever. Those who have lost their way have no intuitive understanding of this; that is why they speak of the methods as though they differed from one another. Fools bogged down in a multiplicity of methods revolve endlessly from life span to life span. I exhort you students to practice the way of relinquishment and nothing else, for it brings to perfection not only the other five paramitas, but also myriads of dharmas (methods).

A Paramita Process – Paradoxical Mobius loops as themes for inner work and group council process:

• 1 – How may I discover SELF, by serving others; How may I serve others, by discovering SELF

• 2 - In giving (dana), mind transforms the gift and the gift transforms mind

• 3 – A method/process on how to experience and discover an inner (spiritual) quality one doesn’t have … give it to someone.

• 4 – Selfless service begins with cleaning the kitchen, sweeping the pathway, planting seeds and watering your garden as acts of generosity / dana.

• 5 - Breathing as dana paramita.

Suggested inner work exercise, list some more examples of dana paramita in the activity of your daily life.

The Bodhisattva Path[iii] –

Generosity / Dana – the Paramitas

• All the activities of a bodhisattva are subsumed under the topic of the six perfections, or paramitas. Each of these paramitas are presented in a threefold manner, as follows:

• The first of the six is the perfection of generosity. Its three aspects are as follows:

• A) giving spiritual teaching or imparting any useful knowledge is generosity in terms of dharma;

• B) giving any material thing … is generosity in terms of material.

• C) giving protection to those who are threatened by any kind of fear is generosity in terms of serving others.

Zen Master Dogen writes, “in giving [dana], mind transforms the gift and the gift transforms mind.”

Dogen on Dana:

“The Buddha said, ‘When a person who practices giving goes to an assembly, people take notice.’ Know that the mind of such a person communicates subtly with others. This being so, give even a phrase or verse of the truth; it will be a wholesome seed for this and other lifetimes.”

“The mind of a sentient being is difficult to change. Keep on changing the minds of sentient beings, from the moment that you offer one valuable, to the moment that they attain the way. This should be initiated by giving [dana]. Thus, giving is the first of the six paramitas [realizations].”

Dogen: Giving and the way of the Bodhisattva

“When one learns well, being born and dying are both giving (dana)”

“Mind is beyond measure. Things given are beyond measure. And yet, in giving, mind transforms the gift and the gift transforms mind.”

“A king [Emperor Tai of the Tang Dynasty] gave his beard as medicine to cure his retainer’s disease. A child offered sand to Buddha and became King [Ashoka] in a later birth. They were not greedy for reward but only shared what they could. To launch a boat or build a bridge is an act of giving. If you study giving closely, you see that to accept a body and to give up the body are both giving. Making a living and producing things can be nothing other than giving. To leave flowers to the wind, to leave birds to the seasons, are also acts of giving.”

The Buddha’s earth touching gesture expresses dana paramita

Dana / Generosity-

the foundation and seed of spiritual development

The Buddha taught that when we give to others, we give without expectation of reward. We give without attaching to either the gift or the recipient. We practice giving to release greed and self-clinging.

"The practice of giving is universally recognized as one of the most basic human virtues, a quality that testifies to the depth of one's humanity and one's capacity for self-transcendence. In the teaching of the Buddha, too, the practice of giving claims a place of special eminence, one which singles it out as being in a sense the foundation and seed of spiritual development.”[iv]

Dana Paramita Overview

• beyond merely giving material goods or donations.

• Encompasses a broad range of selfless acts.

• Selfless sharing of time, knowledge, compassionate support, and wisdom teachings (Dharma).

• Dana encapsulates our altruistic motivation to give without the expectation of reciprocation or personal gain.

• A seamless activity where the person, activity of giving and the result are selflessly unified

The ‘Near Enemies’ of the Paramitas

• Dana / Generosity versus dysfunctional co-dependency

• Sila / harmony-ethics versus moralistic prescribed fundamentalism

• Kshanti / Patience versus denial; covert ‘cocooning’; passive evasiveness

• Virya / Courageous selfless energy versus ego driven fanaticism

• Vairagya/ Dispassion/ non-dual equanimity; versus depersonalized disconnection

• Dhyana / meditation – contemplative equanimity versus a subjective escapism bypassing deep emotions and samskaras

• Prajna / Wisdom equals a direct Gnosis /experience of our essential heart-essence, versus Ideological replication and dogmatic fixations masquerading as ‘wisdom’.

Additional inner work exercise: in your listing of dana paramita examples see where the ‘inner near enemies’ of the paramita appear. Remedies for the near enemies of the paramitas are not formulaic and unique for each person, yet gradually through further zazen, integrated with insight, our paramita practice evolves with more depth and naturalness. The challenge of integration is to keep chewing on the food of our insight in order to digest it thoroughly.

“When your unenlightened nature arises, don’t compare it to this or that. Zazen will teach you so let it be.”[v]

[i] Dogen Zenji – Founder of Soto Zen in Japan 1200-53.

[ii] Dazhu Huihai 大珠慧海 713-812 - A Treatise on the Essential Gateway to Truth by Means of Instantaneous Awakening translated by John Blofeld

頓悟入道要門論 Dunwu rudao yaomen lun

[iii] Doboom Tulku – The Buddhist Path to Enlightenment p182

[iv] Theravadin monk and scholar Bhikkhu Bodhi

[v] Kozen Kato – The Old Buddha Kozen Kato by Arthur Braverman p. 102

Peace Practice Series: Peaceful Dharma / Violent Drama

Cultivating Inner Awareness

for Outer Peace

By Kenneth Small

“Gradually discover how to harmoniously release our inner hostages of latent harmful emotions”

Modes of Inner Peace: Aphorisms, Insights and a Story

Introduction

During our daily activity how aware are we in our mundane communications and interactions of being truly present? Driving the roadways, shopping at the grocery store, riding the transit, at a restaurant, with family and friends… how truly present are we or how often are we habituated with our attention distracted and somewhere else? How often do we fill in the ‘gap of preoccupied distractions’ with fear, self-loathing, anxiety, prejudice or anger…? How often do we justify these emotions when a convenient target or trigger to hang them on comes by? … whether personal, family or group based. How may we engage in filling in this gap with wonderment, compassion and (as the popular saying goes) genuine ‘random acts of kindness’? And… the nitty gritty, how may we discover genuine inner peace and tranquility, which may even gradually, when skillfully and harmoniously harnessed, release our inner hostages of latent harmful emotions that feed collective violence and war? How is it possible to evolve these semi-unconscious, often entrenched cultural complexes and transform them into a higher purpose? A courageous deeper dive into a universal inclusive View, combined with inner contemplative and transformative practices provides tools and solutions to heal these inner rifts. These contemplative tools united with deep universal ethics are essential. The value of contemplative practice is multi-faceted, with traditions around the globe to discover these inner resources within. One of the central human benefits found in all genuine contemplative practice is that the daily practice gradually de-compartmentalizes our human fixations, personal and even group / collective complexes that house our greed, anger, fear and trauma. Contemplative practice when skillfully integrated with a Universal View is key.

How to apply the ethics of peace in our often-fragmented world today (2024) is more and more imperative and the solution is within each one of us, with no action insignificant. Wars are but the expression of internal ‘psychic events’ and their solution is within this same internal arena.

Sri Krishna Prem[i] writes:

“Wars are psychic events that have their birth in the souls of men. We like to put the blame for them upon the shoulders of our favorite scapegoat, upon imperialism, nationalism, communism or capitalism, whichever be our chosen bogey. Not any or all of these are really responsible, but we ourselves, we harmless folk who like to think that we hate war and all its attendant horrors. … Every feeling of anger, hated, envy, and revenge that we have indulged in, in the past years, has been a handful of gunpowder thrown onto the pile which, sooner or later, explode as now [1940’s WWII] it has done.”

All humans contain unconscious displaced obstructive elements[ii] which turn into often harmful projections. Engaging our center through contemplative silence opens doors where ‘eating’ our ‘shadow’ becomes not only palatable but centrally nourishing and benefits the common good. We gradually discover how to harmoniously release our inner hostages of latent harmful emotions.

The poet Robert Bly gives us a view of our inner and outer worlds interlinked with inner process. For outer peace we need to reclaim our ‘projected material’ through creative expressions, through language, art, music, poetry etc.:

“People who are passive toward their projected material contribute to the danger of nuclear war, because every bit of energy we don’t actively engage with language or art is floating somewhere in the air above the United States [and globally ed.] …”

“Eating our shadow is a very slow process. It doesn’t happen once but hundreds of times.’ [iii]

Contemplative inquiry and practice give us the tools to reclaim our lost and often toxic ‘projected material’. This becomes the firm foundation for outer peace.[iv]

Transformation through Deep Contemplative Practice

A Story

– the Korean War Veteran, Mercenary

It was a wilder time, the early and mid-1970’s, also in a special way there was at times more openness to a sense of freedom for greater risk taking, necessary for both inner and outer transformation. Our current time sees some of this flavor returning (2024). Our story is about Jim (I will call him) who was a Korean war veteran. During the Korean war time he had once been sent to blow up a bridge above a river, prematurely interrupted by the approach of enemy troops, to save his platoon, he had to detonate the explosives while he was still under the bridge. Found a day later, Jim had somehow survived being washed down the river without drowning. He was bold, carefree, but inside hardened and had become fanatical, espousing extreme views. He wrote for extreme periodicals spewing hateful rhetoric, engaged in semiprofessional boxing and became a mercenary in central Africa in the late 1950’s. Inside Jim, there was deep trauma and anger. One day around 1970, with his family, he was out on a mountain hike and ended up inadvertently walking along a pathway through the small cabins of the Hermitage[v]. It seemed empty but something about the silence drew his curiosity. Suddenly the Abbot appeared in his formal robed attire, he was Austrian with piercing blue eyes, his sternness and resoluteness was set within a deep pool of presence and being. Jim asked him curiously: ‘What is this place? What do you do here’ The Abbot replied tersely: ‘You wouldn’t be interested… it’s too difficult for you…’ and began to walk away. Jim stunned, persisted and the Abbot abruptly replied, ‘We have a weeklong meditation retreat in a month… you won’t be able to get through it… this is more challenging than anything you’ve ever done in your life’ and as suddenly as he had appeared the Abbot was gone. The Abbot had penetrated Jim’s armor and Jim couldn’t get the retreat out of his head. In the following weeks, he was hooked, had vacation time coming and decided to go on the retreat, knowing absolutely nothing about what he was getting into. By mid-week the silence was killing him, his body ached and the incomprehensible short interviews with the head Teacher were driving him crazy. A few years later he shared with me (by then with a calmness smiling at his own foolishness) how all he could think of mid-week during his first retreat was how he could get away with killing the Teacher, whose unanswerable questions were maddening to him and then finish off everyone else and escape without getting caught! Jim made it through, but ‘something’ had shifted inside, and he was ‘hooked’. A few months later he went again and yet again, more and more each year. He then took off from work to live for an extended time at the Hermitage, gradually engaging deeper and deeper penetrating through his trauma and anger. During retreats he would sometime vividly relive his wartime traumas, perspiring, even reliving hallucinatory events and shaking, yet he remained steadfast in his meditation practice through these episodes and persevered. They gradually melted, losing their grip on him and his anger, prejudice and fears subsided. They were not replaced with some kind of fabricated or artificially fake overlay but transformed. Jim’s strong irascible character remained with a courageous spirit bent toward being Awake in this moment. Jim settled into a lifestyle that integrated his spiritual meditative practice where his anger and prejudices and extreme views and traumas melted away. There were still ups and downs and challenges, but his personal life had gradually become more settled and content. In his mid-eighties Jim passed away peacefully.

[i] Initiation into Yoga p. 103 by Sri Krishna Prem (Ronald Henry Nixon 1898-1965) a Quest Book, the Theosophical Publishing House, Wheaton, Illinois / Chennai, India.

[ii] In Buddhism, these are the samskaras or ‘inciting nafs’ of Sufi tradition.

[iii] A Little Book on the Human Shadow by Robert Bly Harper and Row 1988, pp. 43, 38.

[iv] Faith and Violence by Thomas Merton - University of Notre Dame Press 1968, pp. 112-13. “The self-affirmation that springs from ‘using up’ something or someone else in the favor of one’s own pitiable transiency, leads to the outright destruction of others in open despair at our own evanescence.

[v] A Zen Buddhist retreat

Korean War Veterans Memorial

The Rainmaker Story:Lecture by Robert Johnson

My first meeting Robert Johnson was in 1970/71, where I joined in with a group of friends to participate in Robert’s weekly ‘young men’s group’. At that time, he was living on his cliff side home in Encinitas, and we would carpool up and back from San Diego. Each week, for several years, we would engage under Robert’s wise guidance in sharing dreams, studying fairy tales and myths, with Jungian views and insights. Reflecting back to this time, I see what a rare and special time, where, through Robet’s quiet guidance and wisdom these small intimate gatherings facilitated our inquiry into the heart of the nature of our inner life. One of the stories he shared with us, The Rainmaker Story, he would later give as a formal presentation to the San Diego ‘Friends of Jung’ group. What follows is an unedited transcript of this lecture. – Ken Small

![ONE EMPTINESS: An Incantation to Benefit Others – (Hsin Hsin Ming[i])Entrusting the Essential ‘Heart-Mind’ ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ed9e7c120cbd9238cf57fac/1730178710238-TZXCMIWZY623MMBF5R5J/Picture1.jpg)

Wabi Sabi Zen

Wabi Sabi Zen is purely natural Zen. It is exemplified in the life of the Zen

hermit Ryokan. (1758-1831) Ryokan’s utter simplicity and directness point us

to a Zen practice that is unaffected by exterior forms and disciplines, into a

natural world of direct experience…

Engaging our Circle of Presencing Emptiness

In Zen culture that developed in Japan the use of the Enso in art and

calligraphy is pervasive, where the Enso circle is the most popular of

calligraphies. The historical roots go back to India, where the initial concept

of zero was represented by the bindu or dot, the intrinsic spirit-life seed

within all reality. This later evolved into the circle or Sunya and then to the

Buddhist paradoxical idea of Emptiness or Sunyata - the ‘empty’ (sunya)

that is completely ‘full’ (ta)…